Continued from Part One: https://writersatlarge.com/riff/reel-healing-pt-1/

Born on April 1, 1883 in Colorado Springs, Colorado, Chaney was the son of deaf parents. His parent’s disability prompted him to develop his pantomime skills, which would lead to a career in theater. He joined his first traveling vaudeville troupe in 1902, married singer Cleva Creighton in 1905, and welcomed a son, Creighton (who would become better known in film as Lon Chaney, Jr.) in 1906. The couple settled in California in 1910.

In 1913, Lon was stage managing the Kolb & Dill show at the Majestic Theater in Los Angeles. On the night of April 30, Cleva appeared and attempted suicide by drinking a concoction of mercuric chloride. The attempt to end her life was unsuccessful, but the chemical ruined Cleva’s voice, and the resultant scandal, coupled with the subsequent divorce, forced Lon out of theater forever and into Hollywood, considered a severe step down from the vastly more respectable live theater.

Although it’s hard to imagine now, film, in its earliest days, was considered a disreputable place for a serious actor. Indeed, although many stage actors appeared in early films – “slumming,” as it would be called today – few if any of them wanted their names attached to their productions, as they feared it would harm their “legitimate” careers on the stage.

This was the environment that Chaney entered when he appeared in his first film, the one-reeler, Poor Jake’s Demise (1913), about a man who finds his wife in a compromising position with another, and ultimately takes his revenge on his wife’s paramour, armed with a bottle of seltzer. An inauspicious debut, Moving Picture World dismissed it by saying, “This is simply horse play without any special appeal, though it is harmless and lacks vulgarity.” But of such humble beginnings are legends born.

From this point until 1917, Chaney was under contract to Universal Studios, gaining a reputation as a reliable, if not exceptional, character actor, whose facility with make-up gave him a leg up in the competitive casting process of the time. In 1915, now making $45 per week at Universal, Lon married Hazel Hastings, whom he had met when she was a chorus dancer with the Kolb & Dill show. This marriage was more successful than his first, and lasted until Lon’s death in 1930. The couple also gained custody of Creighton, who had been living in various boarding schools since his parent’s divorce.

Lon’s list of credits at Universal grew over the next few years, as did his salary ($75 per week by 1918) and his reputation with the movie-going public. When he asked studio manager William Sistrom for a raise to $125 per week and was refused (Sistrom told Chaney he would never be worth $100 per week), Chaney left the studio. After several worrying months without work, Chaney landed the role of Hame Bozzam in the William S. Hart picture Riddle Gawne (1918), and his fame and career began to skyrocket. His portrayal of The Frog cemented his status as a true Hollywood star. But the best was yet to come for Chaney.

In 1920, Chaney took on what was arguably the most challenging role of his still-young career, that of the criminal mastermind Blizzard in The Penalty (1920). Based on a book by the then-popular writer Governeur Morris, the story is about a boy injured in a traffic accident, suffering injuries to his head and legs. An inept and inexperienced surgeon is called to his aid, and unnecessarily amputates both of the boy’s legs above the knees. The boy’s bitterness at his affliction turns to evil, and he becomes Blizzard, the chief of the underworld in San Francisco’s Barbary Coast, a haven for criminals, gangsters, prostitutes, and other assorted reprobates.

Chaney created the legless Blizzard by using an ingeniously designed costume which allowed him to strap his lower legs behind him and place his knees in leather stumps, so that, actually walking on his knees, it appeared to the audience as if the actor was truly a paraplegic

The rig was extremely painful, and Chaney could only act in it for short periods of time before having to divest himself of the costume and receive massage on his legs. Nevertheless, even today, a century later, watched through the eyes of someone accustomed to CGI and other forms of special effects, Chaney’s athletic portrayal is extremely convincing. A gifted and accomplished pianist, Blizzard creates beautifully tortured music, aided by his favorite girl, Rose, who operates the piano’s pedals for him. When he falls for Rose, who is actually a Federal agent sent to infiltrate his organization, her ability to work in tandem with him to make music prevents him from killing her, even when he finds out who she truly is. “I can murder anything but music,” he says at one point during the film. While most criminals of the silent era (and even today) were one-dimensional and irredeemably evil, Blizzard has a gentle side, in stark contrast to the cruelty he has displayed so vividly earlier in the film.

“…Chaney reminds the audience that even those who seem frightening due to their outer appearance often possess souls of radiant beauty.”

What’s significant here, then, is the timing of the release of The Penalty. By 1920, World War I was over, and the veterans that had fought so hard and sacrificed so much were coming home, many “lucky” to have only suffered the loss of limbs, others even more disfigured. Viewed by many as “monstrous” (even those who “only” suffered missing limbs were often seen as less than human), Chaney reminds the audience that even those who seem frightening due to their outer appearance

This is important, as contemporary sources report that the reaction to these wounded vets by the public could be extreme. Nurses had trouble looking at their patients, children screamed and ran from their fathers and brothers, and some vets refused to see their families at all for fear of their response.

Even more important, however, is Chaney’s complex and layered creation of Blizzard. Evil, cruel, and despicable as his actions make him, Chaney imbues the crime lord with a tender soul, one revealed under only the most private circumstances.

As Susan Biernoff discusses in her essay, “The Rhetoric of Disfigurement in First World War Britain,” the disfigured face, it turns out, is not equivalent to the wounded body. Although both are considered abject – in that, as described by psychoanalyst and semiotician Julia Kristeva, the violated face causes a breakdown in our idea of conventional identity and causes a symbolic collapse in our ingrained concept of Self and Other – the disfigured face is somehow more abject, and thus more repulsive to us.

“…the face is the repository of much of an individual’s sense of self, of identity…”

It must also be recognized that the face is the repository of much of an individual’s sense of self, of identity, and serves as the most basic form of communication. Take all that away, and what is left of a person? The face bears a complex amount of data about each individual, such as gender, age, social identity, race/ethnicity, emotion, and more, all of which helps to establish who and what that person is, both to the individual and to others. With that removed, the ability to relate to others in any kind of meaningful way is handicapped, forcing one to the fringes of society, othered in a world that places so much value on appearance. For this reason, facial injuries have largely been considered the worst kind of wounds.

Not surprisingly, the craft of mask making for vets who had suffered such wounds advanced greatly during this time, but even the finest craftsmen were only able to approximate – and never duplicate – the original features, resulting in a descent into the Uncanny Valley in which the final product was, in a way, almost as disturbing as the wounds themselves. The character of Richard Harrow (played by Jack Huston in the HBO drama Boardwalk Empire), a veteran of the war whose face had been horribly mutilated, wore such a mask, and part of his character arc was the slow but steady dehumanization Harrow experienced before ultimately committing suicide. His disfigurement, even when alleviated by the mask he wore, separated him from society, and marked him as an “other,” in spite of the patriotism and heroism that was spoken to by such a wound. Even though he eventually found a small circle of friends, and, indeed, the love of a fine woman, Harrow was never able to overcome the effects of his wounds, and was never able to truly fit into the society he left to fight the war. Perhaps inspired by Chaney’s earlier work, Harrow is a complex character, at once both a cold-hearted, cold-blooded killer, and a tender, loving man who cares deeply for his friend’s orphaned child and longs for a family of his own.

The Penalty was only the first example of Chaney’s humanizing of monstrous characters. He would revisit the theme often, pulling at the heartstrings of the audience in an attempt to delve past the outer trappings into the soul of the “gargoyles” he portrayed. Indeed, these are some of his most luminous creations, and the ones that continue to thrill audiences to this day.

Following The Penalty, Chaney’s next foray into the realm of the disfigured came in 1923, when he essayed the role of Quasimodo, the deformed bell-ringer in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, an adaptation of Victor Hugo’s well-known novel, Notre Dame de Paris. Abandoned on the steps of Notre Dame Cathedral as an infant on Quasimodo Sunday (the first Sunday following Easter), he is taken in by Archdeacon Claude Frollo who, naming the baby after the day on which he was found, raises him to become the ringer of the church’s bells, an occupation that eventually costs the child his hearing. Although Hugo describes Quasimodo as “hideous,” and a “creation of the devil,” he is also shown to be kind and loving.

This, then, was a perfect character for Chaney’s skills. Using his make-up artistry, Chaney created one of the most indelible characters ever to grace the silver screen, with a shock of unruly red hair, a blinded eye, massively built-up cheekbones, jagged teeth, and a huge hump on his back. Especially when stripped to the waist for flogging, which reveals the thick, dark hair that covers his chest, Chaney’s Quasimodo appears as something other than human.

However, the Hunchback’s tragedy has less to do with his appearance than it does with his heart, as he has the misfortune to fall in love with the beautiful gypsy girl Esmerelda (Patsy Ruth Miller). Of course, Esmerelda only has eyes for the dashing Phoebus (Norman Kerry), setting up the love triangle and the theme of unrequited love that would mark so many of Chaney’s pictures. Once again, the theme of the monstrous and disfigured shell that hides a tender and loving heart is addressed, paralleling the real-life issue of the often horrific outer appearance of disfigured vets versus their true nature.

A similar theme underlay The Phantom of the Opera (1925),2, and Chaney’s portrayal of Erik, the scarred and disfigured “Opera Ghost” who lives below the Paris Opera House in a maze of rivers and catacombs, and who has fallen in love with up-and-coming diva Christine Daae (Mary Philbin). Erik trains her in secret, never appearing before her as anything other than a disembodied voice in order to avoid what he knows will be a horrified reaction when she sees his blasted face. Over time, he begins to believe that she might love him as well, and makes preparations in his underground empire for their life together. Not surprisingly, Christine has become enamored of the dashing Raoul, Comte de Chagny (Norman Kerry). Nevertheless, Erik makes plans to introduce himself to Christine, leading to a tender scene in which he lures her backstage after a performance. As she stands in the darkness awaiting her teacher, we see Erik stealthily approach her. Then, in shadow only, we see Erik’s hand slowly and cautiously reach out to Christine, as if to touch her. We understand that this is a crucial moment for Erik, the moment when all of his desires will either be damned or rewarded.

Chaney effectively communicates this by imbuing the simple act of reaching out with an abundance of emotion. Then, at almost the last minute, the hand draws back, signifying that Erik, the “ghost” who has terrorized countless people, is himself terrified of this small, willowy girl. It is a character-defining moment, acknowledging the fear that many who had suffered disfigurements must feel when confronted with such an occasion. For all the truly monstrous deeds Erik commits later on, the carnage and havoc he creates, this moment is the one that truly gives us insight into a soul tortured by the fact of his horrific visage. One can’t help but feel sorry for Erik, as well as for Quasimodo, when they meet their predictable ends at the conclusion of their respective films.

Rather than ending on a triumphant note, as when Cody Jarrett meets his fate atop the gas storage tank at the end of White Heat (1949), or when the Wicked Witch is dissolved by a pail of water during the finale of The Wizard of Oz (1939), we feel compassion for Chaney’s characters. We intuitively understand that his characters are not evil, but misunderstood, and that their deaths come at the hands of a public that rejected and despised them. Therefore, unlike Jarrett and the Witch, whose ends come about due to their own evil machinations, we, as a society, are indicted in the deaths of Erik and Quasimodo, indicted for our lack of care, our cruelty, and our inability to see below the surface.

Both The Hunchback of Notre Dame and The Phantom of the Opera were Universal Super Jewel productions, meaning that they were “no expenses spared” films, much like today’s blockbusters. Thus, they were seen not only all across America, but around the world. By the time Phantom was released, Chaney was one of the top stars in Hollywood, whose pictures were eagerly awaited by an adoring public. Far from niche pictures, these were the “must sees” of the day. If Chaney had been a star prior to Hunchback, he now had earned the appellation “superstar.”

Chaney would go on making pictures like this throughout his career. In The Road to Mandalay (1926), Chaney plays Singapore Joe, a scarred, half-blind, and wheelchair-bound criminal who runs a crooked dive bar. He falls in love with a woman (who, unbeknownst to him, is his daughter), but she, of course, loves another. This leads Joe to kidnap her fiancé, the Admiral, to prevent them from being wed, but during a fight with the Admiral, Joe’s daughter stabs her father.

When Joe’s criminal associates try to steal the girl for their own purposes, Joe’s better nature arises, and he holds them off long enough for the couple to escape. Joe dies, happy in the knowledge that his sacrifice has resulted in his daughter’s happiness. Based on a rather melodramatic (and improbable) plot, the film still speaks to the inner goodness of someone whose outer form is, at first, a reflection of his embittered and dark spirit, one that is finally overcome by his long-buried “heart of gold” and love for his daughter.

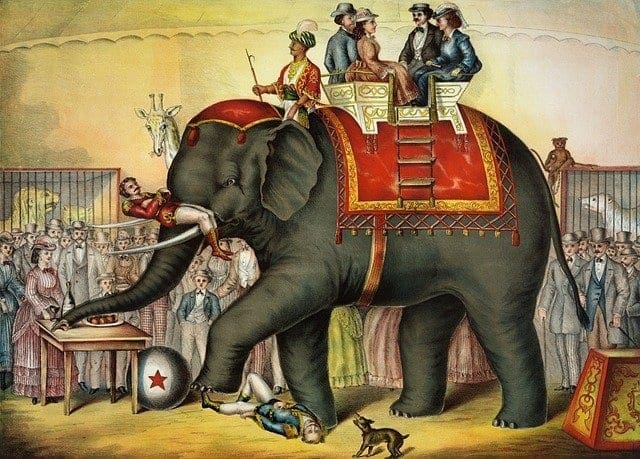

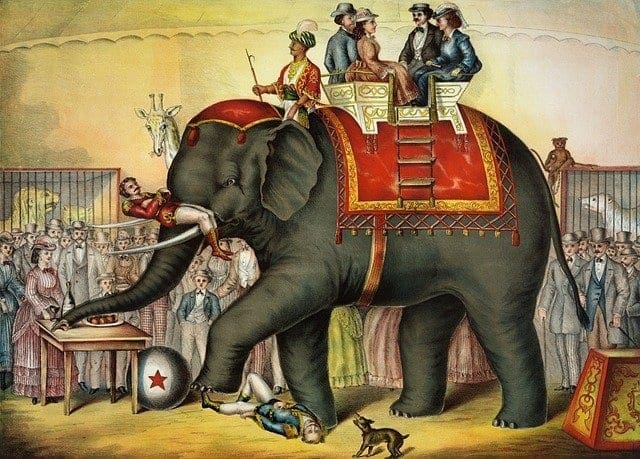

The Unknown (1927), directed by Tod Browning, is perhaps Chaney’s strangest film, and one that deserves special consideration as it relates to the disabled and disfigured. As Alonzo, Chaney is one of the main attractions in a travelling circus: an armless knife thrower. This, however, is merely a disguise. Alonzo is, in fact, hiding from the police for a murder he committed years before. The double thumbs he bears on both hands would instantly identify him to the police, so he keeps his arms tightly bound to his sides as he throws knives with his feet. Alonzo is in love with Nanon (Joan Crawford), whose father owns the circus. The fact that she suffers from a debilitating fear of men’s hands and arms means that she instantly befriends Alonzo, as she never needs to fear him (or so she thinks). But the circus strongman, Malabar (Norman Kerry) also loves Nanon. Naturally, she turns him down due to her phobia. In an effort to undercut Malabar’s romantic efforts, Alonzo encourages the strongman to boldly take Nanon into his powerful arms, hoping that this will drive the beautiful girl away from Malabar forever.

However, Nanon’s father discovers the secret of the knife-thrower’s double thumbs, and Alonzo strangles him to protect himself and his secret. Nanon witnesses the murder, but she can only identify the killer by his double thumbs, not as Alonzo. Realizing that Nanon could never love him because of his arms, Alonzo blackmails a surgeon to actually amputate his limbs, to make himself more attractive to the object of his affections. When he returns to the circus after a period of recuperation, Alonzo discovers that, with the strongman’s help, Nanon has overcome her phobia of men’s arms and is in love with Malabar. In fact, she has agreed to marry him. Now entirely unhinged, as he has crippled himself for no reason, Alonzo plans his revenge, to take place during Malabar’s act in which he attempts to halt two galloping horses on opposite treadmills. The murderer sets a brake on the platforms, intending that the horses will rip Malabar’s arms from his body as they run uncontrollably. But, at the last moment, when Nanon tries to save her lover by quieting the horses, putting her own life in jeopardy, Alonzo, spurred by his love for the beautiful girl, shoves her out of harm’s way and rescues Malabar, at the cost of his own life as the horses trample him to death.

There’s much to say about this film in terms of disability. Alonzo, prior to his operation, is a criminal and a murderer. His double thumbs not withstanding, he is, for all intents and purposes, a normal man playing the role of a disabled person.[3] It is hardly surprising, then, that the film should view such people – those who would pretend to have a disability in order to profit, or, in this case, to hide from the law – with scorn and disdain. The Alonzo we meet initially is clearly a villain, not least for his impersonation of disability. He is bitter and scheming, ready to kill to protect himself, without regard for the lives of others. He is every bit as evil as Blizzard was in The Penalty.

However, when Alonzo has his arms amputated, thus truly becoming disabled, his better nature is allowed to rise to the surface. Not instantly, of course, but in time to selflessly save the life of his former rival. Again, the “heart of gold” shines through the disability, no matter how horrendous that disability appears to others.

Interestingly, by joining a circus[4] and its attached sideshow, Alonzo surrounds himself with a community of similarly deformed and disabled individuals, in the same way that the French veterans did when they joined the Union des Gueules Cassées. Of course, Alonzo’s membership in this society is false, making him “othered” in several significant ways. First, his doubled thumbs set him apart from society at large, as did his status as a murderer and criminal. His status as a non-disabled person set him outside the society of the sideshow, which was populated with such attractions as conjoined twins, bearded women, giants, dwarves, and other “freaks,” as such performers referred to themselves during the heyday of the sideshow. Literally, then, Alonzo belonged nowhere.

British and American soldiers who returned home with facial disfigurements faced much the same dilemma: the Army cast them out stating that their appearance was bad for troop morale, the public wanted nothing to do with them as they were visual reminders of a horrible war that most preferred simply to forget, and even their families, in many cases, rejected them due to their appearance. Without even the support of national groups like those found in France and Germany after the war, these vets were literally “men without a country,” as they struggled to find their way in a society that did not understand them and, worse, did not want them. Even their custom-made masks did little to hide the reality of their injuries. In his autobiography, A Surgeon’s Fight to Rebuild Men (1943), Fred Albee, a pioneer in the field of bone surgery, writes, “…the psychological effect on a man who must go through life, an object of horror to himself as well as to others, is beyond description… it is a fairly common experience for the maladjusted person to feel like a stranger to his world. It must be unmitigated hell to feel like a stranger to yourself.”

But Chaney’s films, some of the most popular of the silent era, allowed people at all social and economic levels to see these wounded warriors in a new light, not as monsters to be feared, but as people as desirous of love and happiness as anyone else. Through the characters that Chaney portrayed, audiences could see their loved ones, neighbors, and countrymen, and look past their deformities and into their hearts with a new regard for their pain and suffering. This, then, could be considered the first step towards healing what had become a national tragedy.

None of this is to say that Chaney, or the producers and directors involved with his films, intended this message of reappraisal and reconsideration. At this far remove, it is fruitless to even attempt such an argument. However, it is not at all improbable to think that these films, seen by so many in America and around the world at such a difficult time, could tap into the zeitgeist of public trauma and address issues of critical importance, even if unintentionally.

Lon Chaney died on August 26, 1930, the victim of cancer most likely caused by decades of heavy smoking. Just a few months later, Universal would begin filming on Dracula (1931), which had, some say, been discussed as a vehicle for Chaney. That was followed at the end of the same year by Frankenstein (1931), which made a star out of a previously little-known actor named Boris Karloff. Intriguingly, Karloff’s Monster was cut from the same cloth as Chaney’s Erik and Quasimodo: a simple creature who wanted nothing more than love, acceptance, and society, and was met instead with violence, hatred, and brutality. In the same way that audiences felt sympathy for Chaney’s creations, they saw beneath the exterior of such Universal Monsters as The Invisible Man, the Wolfman, the Bride of Frankenstein, the Werewolf of London, and Dracula’s Daughter, all marked by a tragedy or monstrous exterior that masked an inner kindness. Chaney had taught Hollywood how to make monsters that weren’t monsters, and the public responded.

There’s no data to suggest that these pictures, and others like them, had any measurable effect on the public’s attitude towards facially-damaged soldiers, but as our outlook on such injuries have tempered over time, it’s reasonable to look at the effect of media, specifically the movies of Lon Chaney, as being a contributing factor. Without the sensitivity of Chaney’s performances, we might still look at the disfigured as monsters instead of seeing their humanity and inner grace. If we as a society have evolved at all in this way, we owe at least a partial debt of gratitude to the great Lon Chaney.

[2] The Phantom of the Opera was literally seen in every corner of the globe between 1925 and 1926, playing on every continent save Antarctica.

[3] In fact, Chaney’s lower body, when performing such feats as throwing a knife and rolling a cigarette with his feet, was doubled by a man named Paul Desmuke [aka Peter Desmuki], who had been born without arms and had learned to use his feet in extraordinary ways. He was, in real life, a knife thrower, as well as a Justice of the Peace. He appeared with the A.G. Barnes Circus & Sideshow and Zack Miller’s Wild West Show, and did his “impalement” knife act with his wife, Mae Dixon, at the 1933 Century of Progress International Exhibition in Chicago.

[4] The circus was an environment with which director Todd Browning was intimately familiar. Born in 1880, at the age of 16, Browning ran away from home, and worked in a variety of circuses (including Ringling Brothers), sideshow, vaudeville acts, and burlesque houses before beginning to work in film as a performer for D.W. Griffith in 1913. He made a number of notable silent films with Chaney, and served a director for Chaney’s only talking picture, the 1930 remake of The Unholy Three. His greatest claim to fame, however, hearkened back to his sideshow roots, the infamous Freaks (1932), starring a number of actual sideshow attractions. The film so upset audiences – one female audience member claimed the film caused her to suffer a miscarriage – that it was pulled from distribution, not to be seen again until the 1960s.

Im happy I found this blog, I couldnt find out any data on this subject matter prior to. I also run a site and if you want to ever serious in a little bit of guest writing for me if achievable really feel free to let me know, im always appear for people to verify out my site. Please stop by and leave a comment sometime!